Not only do I work with ancient computing history at home, but I’m also called upon on occasion to work the deep magic on artifacts floating around the office.

See, where I work has been in operation since 1999, and in that time we’ve acquired literal tons of old computing hardware – that I am currently going through and disposing of.

Part of the disposal process is pulling the drives out of machines with Windows XP licenses on them that are slated for the recycler, and then zeroing out those drive for security – which puts one face to face with a pile of sub 100 gig IDE hard drives.

Yes, the computer on my desk at home has more ram than most of these machines I’m working on today have in total storage…

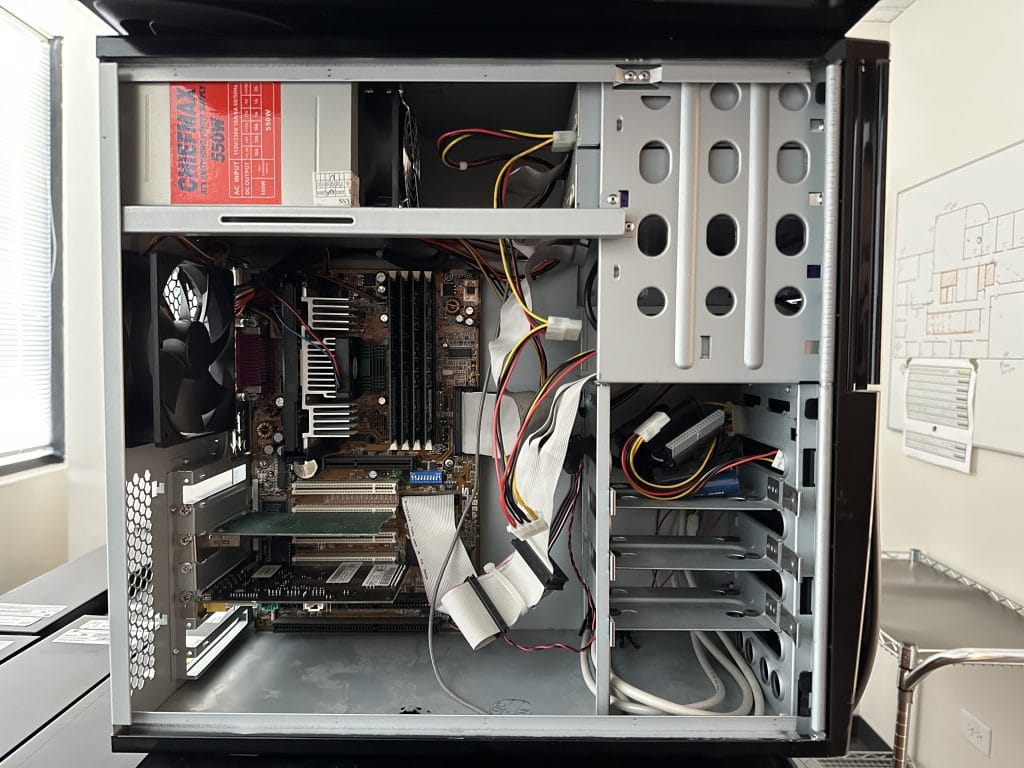

Today I’m going through a bunch of test machines from the old Hardware Compatibility Lab – a lab that we used to run to test software against chipsets for motherboards, video cards, sound cards, etcetera. These test machines date back to the turn of the century and include things like this:

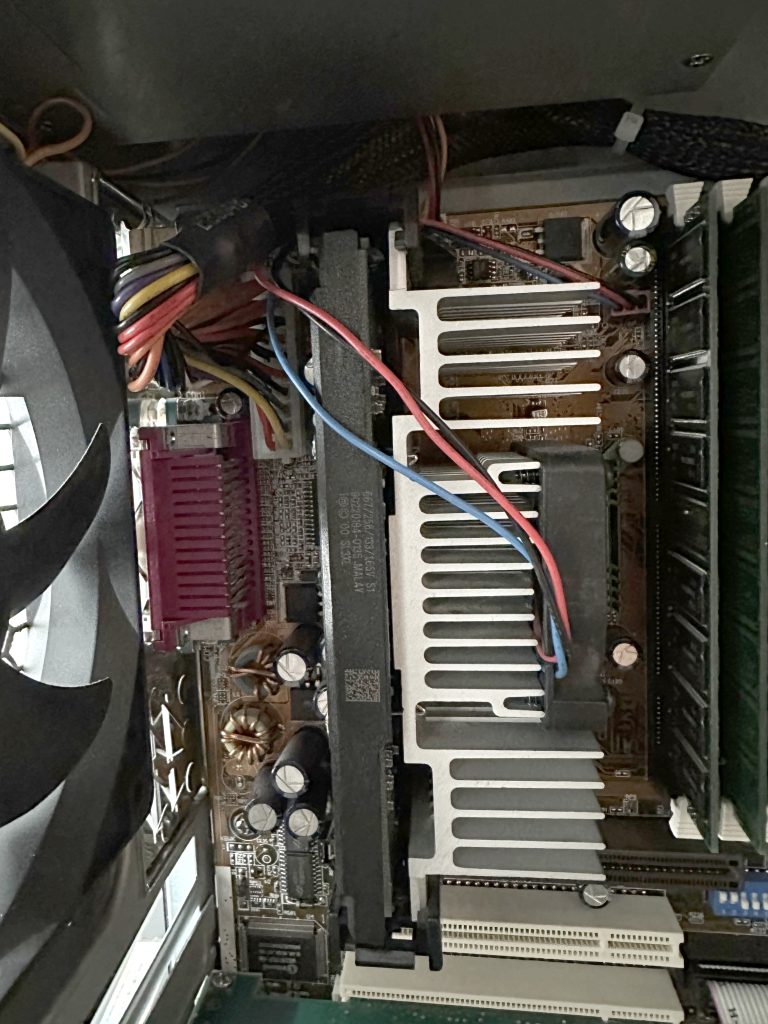

Here’s a closer look at the Slot-1 CPU for anyone who may have never seen one:

Yes, it really is a card mounted in a riser socket… They did this to try and improve cache response for the CPU by making it all integrated. Early Pentium Pros integrated CPU and cache ram on the same substrate, but it was an expensive process. So the fiberglass PCB was an attempt to do the same, but be less expensive.

The Slot-1 / Slot-A (For the AMD versions) was pretty short lived as ram and the associated interconnects quickly became better, allowing Pentium Pro style CPU/cache integration at less cost. So, you only really see these between 1996 and 2000.

The above machine is a 440BX chipset, making it circa 1998.

Anyway, I’m in the process of wiping the IDE drives out of these machines, which calls upon esoteric knowledge of things like cable select jumpers and understanding drive geometry to get a modern machine to understand how to write a zero to every sector on the drive.

So here we have a circa 1999 20 gig IDE drive connected to a circa 2010 IDE-to-USB adapter, which is then connected via a USB to thunderbolt adapter to a circa 2025 M3 MacBook – where I’m using a terminal to talk directly to the BSD underpinnings of MacOS to run a sector-by-sector wipe of the HD.

The can of throwback 80’s Cherry Diet Coke is purely for scale. 🙂

A few of the drives were suffering from “Stiction”, where the heads become stuck to the platters through simple vacuum… The head surfaces and platters are so smooth that when the heads on older drives land, and then the drive doesn’t move for a long time, the heads stick.

Newer drives don’t suffer from this as the heads are offloaded from the platters when they power off. But old dives actually landed the heads on the platters in a parking area.

Being as I was zeroing out and then disposing of the drives anyway, the easiest method to defeat stiction was to simply open the drive and manually turn the platter(s) a bit by hand…

It’s hard to tell in the above image, but the drive is running and slowly stepping the heads across the platters as I zero everything out. The platters by the way are spinning at 5400 RPM.

Here’s a short video that shows how fast the heads moved 25 years ago… This is slow by today’s standards.

Leave a Reply